All Photos Courtesy and © Steven L. Cantor Unless Otherwise Noted

Building Green in Copenhagen

It was my good fortune to visit Copenhagen for 10 days from late October to early November, 2015, on a trip in which I was sponsored by ZinCo, GmbH.

A few days after my arrival, I gave a lecture on the impacts of the High Line (its green roof is a ZinCo product) at the Urban Green Conference, Denmark’s largest trade fair on sustainability.

The conference was hosted for several days in the Forum, a large exhibition venue of about 5,000 square meters on two floors, which has been renovated several times in order to host concerts and other events.

My presentation was a summary of some of the content taken from the series of analytical and photographic essays which I wrote for Greenroofs.com in 2013 – 2015, with some new material, such as additional images from more recent walks on the High Line.

An engaged audience at Building Green.

Chatting with fellow speaker Per Malmos; photo courtesy of Malmos.

The ZinCo booth at the Building Green Fair.

Lots of activity at the Building Green Fair.

The new offices of Malmos

The night before I returned to New York City, I shared a lecture on green roofs with Per Malmos, the president of Malmos and Heidrun Eckert, Business Unit Manager for Scandinavia for ZinCo. We spoke to about 40 invited guests at Per’s new office space for Malmos, which features a green roof and other amenities.

A view of the Malmos greenroof from inside; October 30, 2015.

Presenting to their professionals. Image: Malmos.

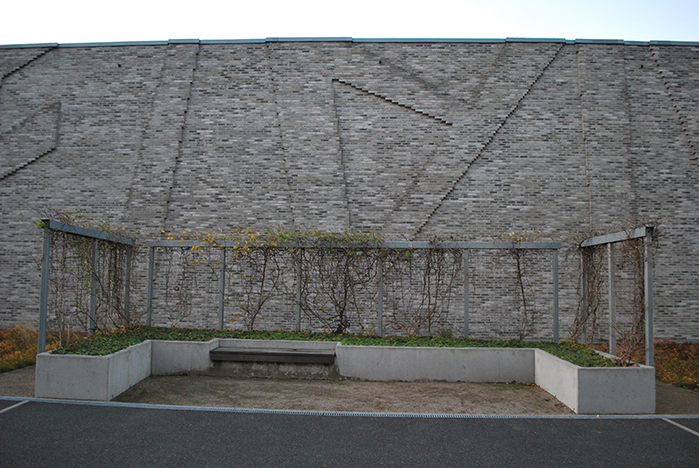

The Malmos Greenwall.

Our mutual goal was to promote green roofs and encourage their use in Denmark’s harsh climate.

A Tourist in Copenhagen

Copenhagen is a major bike city; this form of transportation is interwoven into its culture. November 3, 2015.

In between these two scheduled activities, I was a tourist exploring Copenhagen and its environs, and was given a tour of some green roofs projects in which ZinCo and Malmos collaborated. I would like to share these projects with the readers of Greenroofs.com.

Copenhagen is both an old and modern city. Large areas such as a rabbit’s warren of cobbled streets with old edifices date from medieval times, yet there are striking modernist buildings, such as the new wing to the Danish Royal Library, called the Black Diamond for its sleek glass and granite form, which opened in 1999 by the architect Schmidt Hammer Lassen. The city has efficient public transportation, including water taxis on the many canals and waterfronts, buses and subways. The cityscape is temporarily marred by large construction sites in the heart of the city where new transit stations are being built. Most buildings are low rise so that the occasional tall structure, whether a hotel or an old landmark, become dominant visual anchors within the metropolis.

A modernist volume: housing for the elderly; November 2, 2015.

Tall structures on the horizon amidst construction.

The pervasive sense of the city’s history was never more apparent to me than while dining at a quaint pizza restaurant named Gorm’s on one of the city’s oldest streets. The floors were not perfectly level, yet everything was cozy and comfortable. Underneath the narrow staircase to the second floor was a framed document identifying the continuous ownership of the building since 1383. I indulged myself in fanciful fantasies about some of the previous tenants over its 600 year history.

The Journey

After departing Newark airport early evening, I found myself arriving at Copenhagen’s international airport in a woozy, sleep-deprived state early in the morning. I took a train to the main Copenhagen station, from which it appeared to be a short and direct route to my hotel, the Imperial. Vast parking lots of bicycles flanked the station. During my stay I found it fascinating how Danes could find their bicycles, when so many appeared identical in color and style, and were scrunched together like pretzels. I was reminded of how baby penguins are able to identify the scent of their parents — or face starvation — amidst throngs of thousands of birds in Antarctica. Perhaps, veteran bicyclists have an innate identifying third sense. It was clear enough to me that I lacked the DNA for such neural pathways. The city has a comprehensive bicycle route system. Even in the historic district where streets are narrower, there is often a standardized lane for bicyclists, set off by curbs from pedestrian and vehicular routes.

My smart phone became idiotic, and would not connect to the Danish Tulia network, but the pedestrian route seemed quite clear from a map in my guidebook. However, I misread (and swapped in my head) the names of two streets perpendicular to my route, Tietgensgade for Istedgade, so walked south instead of north along the main thoroughfare for about a half an hour. A kind woman re-directed me.

I back-tracked past the train station, continued on, and walked into the Imperial Hotel. By that time it was nearing lunch time, and I was quite surprised to be greeted in the lobby by a handsome waiter in formal dress who offered me a martini, “shaken, not stirred,” enunciated in better English than my own. Since I was pulling along a Travel Pro luggage on wheels and carrying a shoulder bag, it was awkward to hold a martini, but not to be denied such a pleasure for the earliest time in memory, I graciously indulged.

Then, I noticed giant video images of Daniel Craig as James Bond, and various graphic displays and gradually realized that I was inside the lobby of a multiplex movie theater celebrating the premiere of the new film, “Spectre.” Someone volunteered in a friendly voice that the Imperial was the largest movie multiplex in northern Europe. Under the influence of the martini, I was still able to inquire about the Imperial Hotel, and was told it was around the block. So, I placed the empty martini glass on a tray carried by an obliging waiter, and typically for me that morning, I exited the hotel by turning right.

I walked and walked, circumnavigated the block and found myself at an entrance labeled “Imperial Hotel.” (Had I exited the theater by turning left, I would have found the hotel in less time than it takes to type this sentence.) About a dozen pots with succulents and other ornamental plants were on display along with twice that many bicycles. I entered and checked into my room. During my entire trip, despite several calls to the smart phone’s provider’s customer service, I was never able to get my phone to function properly outside the hotel. The hotel’s WIFI functioned as expected, but once I exited to the street, no amount of settings adjustments or discussions with other phone users resolved the problem. So, I set my schedule every evening and morning, and texted people. I was never able to use the phone to talk to a soul, nor was anyone ever able to call me. Yet, this was my only negative experience of the entire trip.

The Green Tour

Malmos has a new office location in the suburbs of Copenhagen. Depending on the nature of their jobs, the staff disperses throughout the region. Given the preponderance of bicycles and public transportation, I was surprised that most employees had long commutes by car to and from work, but a major factor is the need for convenience to reach meetings and construction sites on short notice.

On the afternoon of my first day in the city, Per came by car with Pernille Kinnunen to welcome me, set the plans for the conference the next day and to start showing me some projects.

Copenhagen’s “High Line”

The Rigsarkivets grønne taghave; October 28, 2015.

Copenhagen’s “High Line” – Rigsarkivets grønne taghave – the National Archives Green Roof Garden, was perhaps a half hour’s walk from the hotel. This long, elevated green roof opened several years ago. It’s called Copenhagen’s High Line, but it’s quite different in concept and execution. About one third of its length is a canyon-like space between the imposing, stark, and impenetrable walls of the Archive Building, whose solid facade affords no entrances.

So, quite unlike New York City’s High Line, no pedestrian traffic is generated by the architectural uses adjacent to it. At the southern entrance, a pedestrian climbs slowly from the street level of the sidewalk to the finish grade of the High Line on a series of ramped concrete platforms lined with narrow beds of planting.

Different perspectives of Copenhagen’s High Line.

Ramped concrete platforms.

Plantings have generally done fairly well, but there have been some problems with trees and shrubs being adversely affected by pollution and soil compaction. There are a few entrances into adjacent buildings. On my two walks on the Danish High Line, once with Per and once alone, I saw a total of perhaps 10 people en route.

As one passes the far end of the Archive Building, the route opens slightly, affording a wider view. There are a few restaurants and housing developments lining the route, but again, they do not seem to be major generators of pedestrian traffic. A few children’s playground areas occur, but it’s not clear where the children would come from to use these spaces. There is little sense of connection to the busy street that runs parallel to the route but some distance away. Some design details provide interesting texture, for example, raised courses in the brick masonry of the Archive Building create linear projections that then cross through the pedestrian pavements in an integrated matter. Yet, these effects often seem too subtle to command the attention of pedestrians.

Pavement details.

Similarly, the plantings are restrained rather than exuberant. Planting beds have clean lines and are clearly marked, usually flush with the edges of pavements, but the plantings themselves, although hardy, have little of the exuberance of the New York City version. There is still potential for this project to succeed as additional phases are being planned, and the route will traverse a range of mixed use architecture and landscape.

Overall, one’s sense of this High Line is that it’s remarkably quiet, and provides a contemplative setting for a small number of pedestrians. It’s an aside, not a main draw. Yet, as the district is developed around it, an increase in use is certainly possible.

One of the few users on my two visits was a skateboarder enjoying Copenhagen’s High Line.

Dusk comes very early in late October, 2015 on the Rigsarkivets grønne taghave.

Malmos has collaborated with the BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group on a number of efforts, so I will focus on those. Some of the text is taken from their website; the reader may wish to check to find additional information, images, and renderings.

BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group

BIG is based in Copenhagen and New York City, and includes architects, designers, builders, and thinkers focusing on architecture, urbanism, research, and development. The firm seeks new ways of creating architectural and urban organization in response to contemporary economic trends and evolving communication technologies and multicultural interactions. (New York City is my home and I plan on visiting some of the firm’s sites and projects in the region.)

Ørestad is a major suburb of Copenhagen. Its development was seriously curtailed by the international recession in 2008, as prices for real estate and apartments crashed; yet there has been a gradual recovery. Malmos and BIG collaborated on a number of projects in this region:

VM Houses

The VM Houses, left, and Mountain Dwellings, right, in the Ørestad district of Copenhagen, Denmark. By 準建築人手札網站 Forgemind ArchiMedia from Taichung, Taiwan, Taiwan (BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group – Mountain Dwellings 01) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

The VM Houses started in 2007 and shaped like a V and an M when seen from above, are the first residential projects built in Ørestaden. The V house is conceived as a balcony condominium, while the M house is an Unite d’Habitation, after Corbusier. The zigzagging M house allows views and daylight in both directions. Openings transform the circulation into attractive social spaces. Balconies are wedge-shaped planes that combine maximum shade and cantilever.

The V building; November 2, 2015.

The M building.

The grouping of balconies creates a backdrop to a community of neighbors. The 225 units are divided in myriad and intricately interlocking ways, so that there are over 80 unique types. As a result of this variation, the facade of the building, far from uniform, despite the strong geometry of the architecture, creates a complex visual composition.

VM Houses in Copenhagen, Denmark. By cjreddaway (110915 PLOT_VM Housing 07) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

Mountain Dwellings

Mountain Dwellings. Photo ©Jens Lindhe, Courtesy of BIG – Bjarke Ingels Group + JDS Architects.

Mountain Dwellings are the 2nd generation of the VM Houses, for the same client, of the same size and located on the same street. However, the program is quite different: 2/3 parking and 1/3 housing. Rather than two separate building abutting each other, the architects merged the two functions into a symbiotic relationship. The parking area needs to be connected to the street, and the homes require sunlight, fresh air and a view. Thus, all the apartments have sunny roof gardens, with striking views.

The mountain appears as a suburban neighborhood of garden homes flowing over a 10-story building, a suburban living with urban density. The mountain includes a number of sustainable technologies. Most notable is that rainwater is collected in an underground cistern and then recycled to be used as drip irrigation throughout the terraced planters.

Rainwater is collected underneath this pedestrian pavement.

Parking is connected to the street and to each individual unit.

The Mountain Dwellings homes have fresh air, greenery, and beautiful views to the suburban countryside.

The multi-hued ramped elevator system of the Mountain Dwellings.

A system of ramped elevators accesses the apartments and parking from the concrete parking garage honeycombed below the housing units. It’s a fascinating experience to approach the apartments from below by using its colorful, ramped elevator system as the living experience of each apartment gradually unfolds.

8 House

Aerial of 8 House, or Tallet; photo courtesy of BIG by ©Dragor Luft.

8 House; photo courtesy of BIG by ©Jens Lindhe.

8 House or 8 Tallet, an apartment building of 475 units completed in 2010, is located in Ørestad South on the edge of a canal with a view of the open spaces near Copenhagen. Its bow-shaped building, like a figure eight script, creates two distinct spaces, separated by the center of the bow which hosts the communal facilities. At this central location the building is penetrated by a 9 meter (30 feet) wide passage that connects two surrounding city spaces, the park area to the west and the channel area to the east.

Apartments are placed at the top, while the commercial facilities start at the base. There are two steeply sloping green roofs over 19,000 SF (1700 sqm) in locations optimal for reducing the urban heat island effect and for visually connecting to the adjacent farmlands. These two green roofs are among the steepest I’ve ever observed, and are well established.

You can appreciate one of the steep slopes of the building.

Looking down into one of the interior courtyards; November 2, 2015.

The second larger courtyard as seen from ground level.

The units have either balconies or small terraces.

Vegetated mats were used on 8 House green roofs.

…opening up the interior courtyard to a view of the protected open spaces of Kalvebod Fælled.

The moss-sedum roof covers the extraordinarily long, steep and sloping roof surface descending 11 floors downward to the edge of a canal in Ørestad South…

At their bases are flatter areas, which being more stable and likely receiving some additional rainwater or irrigation runoff, have the densest growth. The shape of the building facilitates natural ventilation of all units and daylighting. Rainwater is collected and re-used through a stormwater management system. The weather was overcast during the afternoon of my visit, but not terribly cold, so I was surprised not to see a lot of street activity, particularly at the commercial level. Perhaps, business activity will increase as the community of which it is a part becomes more vibrant and attractive.

Photo courtesy of BIG by ©Ty Stange.

Spectacular views of 8 Tallet from the Copenhagen Canal; photo courtesy of BIG by ©Jens Lindhe.

Amager Resource Center (ARC)

The Amager Resource Center; November 2, 2015.

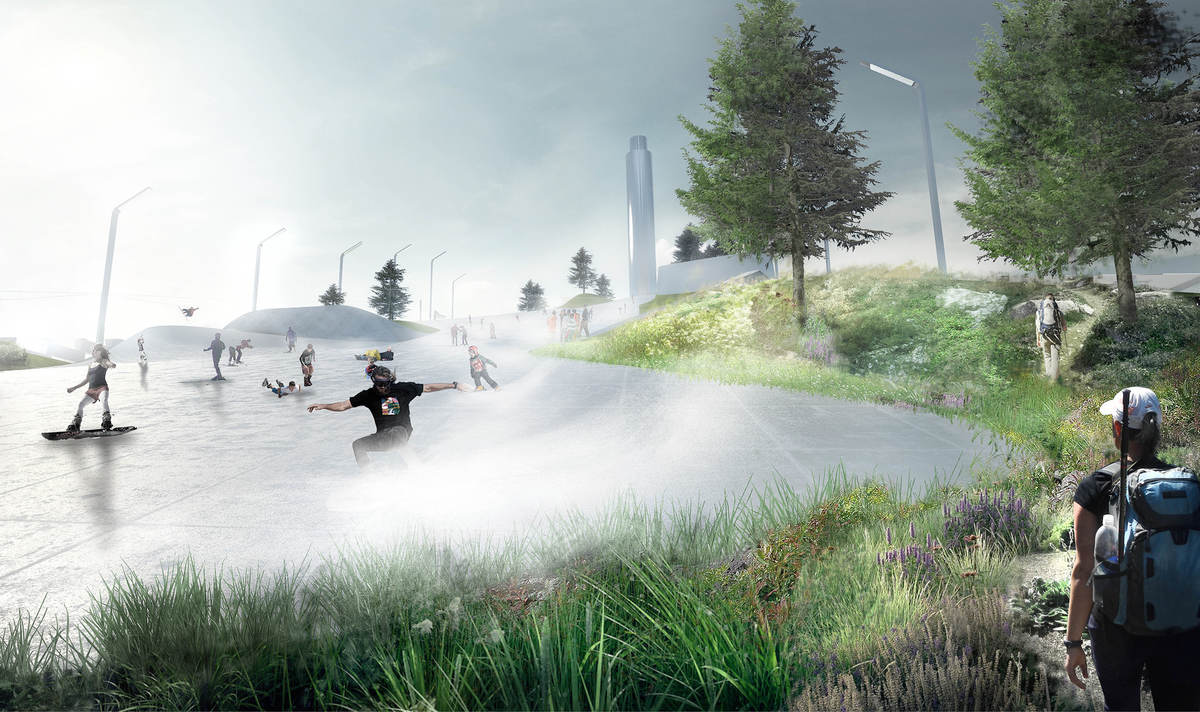

The ARC, now under construction, a waste-to-energy plant, is located in an industrial area of Copenhagen that has evolved into a destination for extreme sports and for thrill seekers. Rock climbing, go-kart racing, cable wakeboarding are all popular. BIG won a competition in 2010 for a building with a space of 41,000 square meters. The ARC will be the most significant landmark in the area, which is in need of renewal. The edifice will be a new breed of water-to-energy plant, one that is economically, environmentally, and socially profitable.

Instead of considering the ARC as an isolated object, the designers have attempted to intensify the relationship between the building and the city, thereby expanding the existing activities into the area by turning the roof of the new ARC into a ski slope for the people of Copenhagen. The new plant established ARC as an innovator on an urban scale, redefining the relationship between the waste plant and the city. It will be both iconic and integrated, a destination in itself, and a reflection on the progressive vision of the company. ZinCo modular units will coat the exterior of parts of the building to form continuous green hanging gardens.

The facade of the building is gently wrapped with a continuous pattern of stacked aluminum bricks. The openings between the bricks let in sunlight deep into the processing hall and the administration space. The bricks on the facade also function as planters, creating a green facade and transforming the building into a green mountain from afar with a white mountain top. The entire roof will be an artificial ski slope where it will be possible to ski all year round. There will be a total of 500 meters of ski slopes. Adapted to the contours of the building’s technological requirements, different areas will accommodate skiers from novices to pros. Access to the ski paths will be via an elevator attached to the smokestacks, and the elevator will have a glass faced wall allowing views of the interior workings of the plant.

The brick facades will be planters. Images: BIG.

By 2017 the Amager Resource Center will be a waste-to-energy plant + mountain + park. The $389 M, 60-megawatt power station will be fueled by Copenhagen’s garbage. Images courtesy of BIG.

As would be typical at a resort, the top of the ski slope area will have a look-out and cafe, and there will be some planted and forested areas, a hiking trail and possibly other amenities, such as a mountain bike trail. A simple alteration to a standard smokestack design will allow it to puff smoke rings whenever one ton of fossil carbon dioxide (CO2) is released. This will be a gentle reminder of the impact of consumption.

Several other remarkable projects or locations were also on my Copenhagen tour:

Amager Beach Park

Copenhagen’s seaside public park, Amager Strandpark. The circular elements are bicycle racks, for which there is a strong need since so many visitors arrive by bicycle; November 2, 2015.

Amager Beach Park – Amager Strandpark – is a seaside public park with a large artificial island and lagoon with various landscapes and amenities created adjacent to Copenhagen’s coastline, near former industrial lands, abandoned as large brown fields, which have gradually been re-developed for high rise housing. The beaches can easily handle 100,000 people on busy summer days. As part of the development, a sheltered lagoon was created in the shadow of the island which is used for practicing sailing and recreational kayaking, since strong winds and waves do not form.

The island is about 2 km long by about 1 km wide. Many of the plant materials, such as willows and grasses, have self-seeded.

Amager Beach Park.

Along the beach are a small cluster of buildings, including three with extensive green roofs: a nature center, a community center, and bathhouse. There are numerous bicycle parking elements, befitting a location where so many beach-goers would arrive by bicycle. Despite the intense exposure to extremes of sun and wind and limited maintenance, these green roofs appear well-established.

The View

The View, multi-family residential housing on November 2, 2015.

The View in Udsigten is the final residential project I was shown. It’s part of a series of residential apartment towers in which the material excavated for basements, foundations, and footings of the building had to remain on the site as part of its landscape structure. Attractive green roofs and roof gardens well-integrated with the architecture are built over the garage in three of these buildings. At the rear of one building is a large ramped fill slope (the excavated material) planted with trees and lawn and gradually becoming established as a recreation area.

My gracious tour guide, Per Malmos.

The View with its large green roof over the garage.

The green roofs have stepping stones, benches, and a few picnic tables. Corten steel barriers are used to set off the fill deposit from the spaces accessible for building residents. An anomaly for a city that seems so self-conscious and celebratory about its architecture is that some remnants of Copenhagen’s medieval walls, which have been exposed during construction of various phases of this project, are not a pivotal design element, but instead, are treated as an afterthought without any link to the modern design or interpretation of its historic context.

Dragør

Dragør’s marina; November 2, 2015.

Dragør, situated 12 – 14 km from Copenhagen, is a historic town of thatched roofs welcoming visitors with many mustard-colored stained walls, a nice contrast to the often cloudy, winter views. Many of the 2 to 3-story buildings have straw thatch (river and sea grasses) which appears quite durable.

Yet, north-facing thatched roofs last 15 to 20 years, while south-facing ones last only about a quarter as long, 3 to 5 years. This underscores the challenge of establishing green roofs in Denmark’s climate, which is prone for harsh winters with heavy snowfall, high winds, and salt spray. For ease of maintenance, there are an increasing number of buildings with tiled roofs.

Dating back to the 12th century, the town of Dragør is a maze of streets and alleys. Shown here are its yellow-hued houses from the 18th century.

Dragør, a former fishing village by the Sound and Baltic Sea, draws crowds of visitors due to its charming, historic nature.

The marina is still active, as it’s the closest in distance to Sweden. Some commercial uses are becoming more established, but the general historic character of the town is well-preserved for the most part.

Copenhagen’s Vocabulary of Sustainability

Other places I visited included the Viking Museum and Cathedral in Roskilde; the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art; the Botanical Garden; the Jewish Museum, the opera house, which looms like a giant ocean liner somehow docked at the canals; the National Gallery of Denmark; several other local parks and museums; and many of the prominent palaces and public buildings in Copenhagen.

Since it’s compact and mostly level, it’s a wonderful city to walk…or bicycle. A vocabulary of sustainability is well-established in the city, and many interesting examples abound.

Copenhagen is a lovely city to visit and live; October 28, 2015.

Perhaps, due to the challenging climatic conditions, green roofs are just starting to become a part of this vocabulary. Given the Danes’ propensity for design, I would expect them to rise to this challenge.

~ Steven L. Cantor

Photos © Steven L. Cantor are available for individual purchase.

Steven L. Cantor, Landscape Architect

Landscape Editor Column

Originally posted on 4/22/16

Photo by Thomas Riis.

Steven L. Cantor is a registered Landscape Architect in New York and Georgia with a Master’s degree in Landscape Architecture from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He first became interested in landscape architecture while earning a BA at Columbia College (NYC) as a music major. He was a professor at the School of Environmental Design, University of Georgia, Athens, teaching a range of courses in design and construction in both the undergraduate and graduate programs. During a period when he earned a Master’s Degree in Piano in accompanying, he was also a visiting professor at the College of Environmental Design at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He has also taught periodically at the New York Botanical Garden (Bronx) and was a visiting professor at Anhalt University, Bernberg, Germany.

He has worked for over three decades in private practice with firms in Atlanta, GA and New York City, NY, on a diverse range of private development and public works projects throughout the eastern United States: parks, streetscapes, historic preservation applications, residential estates, public housing, industrial parks, environmental impact assessment, parkways, cemeteries, roof gardens, institutions, playgrounds, and many others.

Steven has written widely about landscape architecture practice, including two books that survey projects: Innovative Design Solutions in Landscape Architecture and Contemporary Trends in Landscape Architecture (Van Nostrand Reinhold, John Wiley & Sons, 1997). His most recent book, Green Roofs in Sustainable Landscape Design (WW Norton, 2008), provides definitions of the types of green roofs and sustainable design, studies European models, and focuses on detailed case studies of diverse green roof projects throughout North America. In 2010 the green roofs book was one of thirty-five nominees for the 11th annual literature award by the international membership of The Council on Botanical & Horticultural Libraries for its “outstanding contribution to the literature of horticulture or botany.” He has been a regular attendee and contributor at various ASLA, green roofs and other conferences in landscape architecture topics.

In recent years Steven has had more time for music activities, as a solo pianist and accompanist. In 2011 he performed a solo piano program at the Winter Rhythms festival at Urban Stages Theater. He’s a regular performer at musicales hosted in Chelsea and other settings in Manhattan. On August 25, 2013, Leonard Bernstein’s birthday, he performed with Stephen Kennedy Murphy a program of excerpts from the composer’s MASS and Anniversaries.

Steven joined the Greenroofs.com editorial team in December, 2013 as the Landscape Editor. In February, 2015 he completed his 14-part series “A Comparison of the Three Phases of the High Line, New York City: A Landscape Architect and Photographer’s Perspective.”

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture

Greenroofs.comConnecting the Planet + Living Architecture